One scientist’s journey from the Middle East to MIT

Through his leadership and vision, McGovern postdoc Ubadah Sabbagh aims to improve the scientific process in the United States and abroad.

“I recently exhaled a breath I’ve been holding in for nearly half my life. After applying over a decade ago, I’m finally an American. This means so many things to me. Foremost, it means I can go back to the the Middle East, and see my mama and the family, for the first time in 14 years.” — McGovern Institute Postdoctoral Associate Ubadah Sabbagh, X (formerly Twitter) post, April 27, 2023

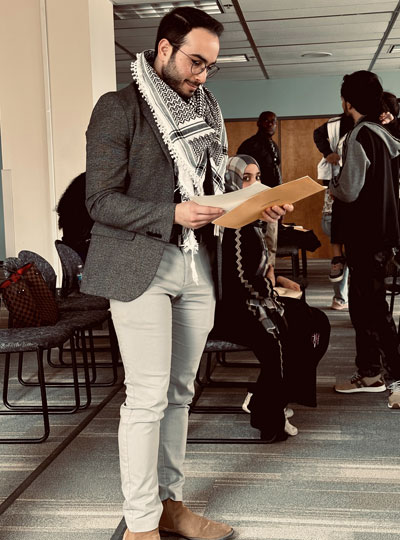

The words sit atop a photo of Ubadah Sabbagh, who joined the lab of Guoping Feng, James W. (1963) and Patricia T. Poitras Professor at MIT, as a postdoctoral associate in 2021. Sabbagh, a Syrian national, is dressed in a charcoal grey jacket, a keffiyeh loose around his neck, and holding his US citizenship papers, which he began applying for when he was 19 and an undergraduate at the University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC) studying biology and bioinformatics.

In the photo he is 29.

A clarity of vision

Sabbagh’s journey from the Middle East to his research position at MIT has been marked by determination and courage, a multifaceted curiosity, and a role as a scientist-writer/scientist-advocate. He is particularly committed to the importance of humanity in science.

“For me, a scientist is a person who is not only in the lab but also has a unique perspective to contribute to society,” he says. “The scientific method is an idea, and that can be objective. But the process of doing science is a human endeavor, and like all human endeavors, it is inherently both social and political.”

At just 30 years of age, some of Sabbagh’s ideas have disrupted conventional thinking about how science is done in the United States. He believes nations should do science not primarily to compete, for example, but to be aspirational.

“It is our job to make our work accessible to the public, to educate and inform, and to help ground policy,” he says. “In our technologically advanced society, we need to raise the baseline for public scientific intuition so that people are empowered and better equipped to separate truth from myth.”

His research and advocacy work have won him accolades, including the 2023 Young Arab Pioneers Award from the Arab Youth Center and the 2020 Young Investigator Award from the American Society of Neurochemistry. He was also named to the 2021 Forbes “30 under 30” list, the first Syrian to be selected in the Science category.

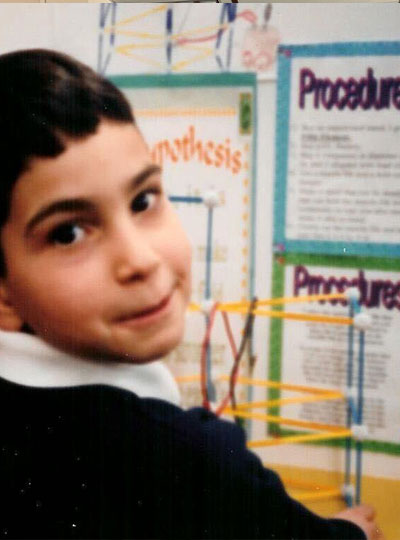

A path to knowledge

Sabbagh’s path to that knowledge began when, living on his own at age 16, he attended Longview Community College, in Kansas City, often juggling multiple jobs. It continued at UMKC, where he fell in love with biology and had his first research experience with bioinformatician Gerald Wyckoff at the same time the civil war in Syria escalated, with his family still in the Middle East. “That was a rough time for me,” he says. “I had a lot of survivor’s guilt: I am here, I have all of this stability and security compared to what they have, and while they had suffocation, I had opportunity. I need to make this mean something positive, not just for me, but in as broad a way as possible for other people.”

The war also sparked Sabbagh’s interest in human behavior—“where it originates, what motivates people to do things, but in a biological, not a psychological way,” he says. “What circuitry is engaged? What is the infrastructure of the brain that leads to X, Y, Z?”

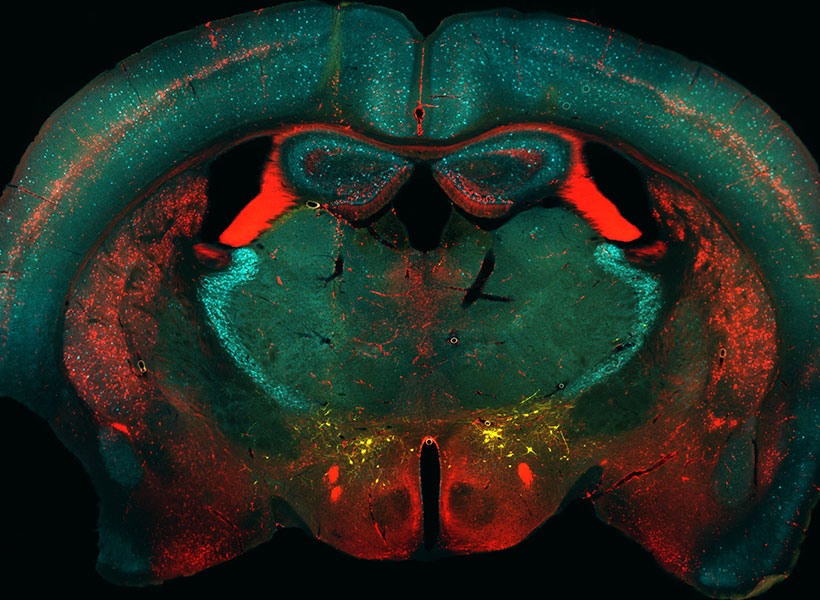

His passion for neuroscience blossomed as a graduate student at Virginia Tech, where he earned his PhD in translational biology, medicine, and health. There, he received a six-year NIH F99/K00 Award, and under the mentorship of neuroscientist at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute he researched the connections between the eye and the brain, specifically, mapping the architecture of the principle neurons in a region of the thalamus essential to visual processing.

“The retina, and the entire visual system, struck me as elegant, with beautiful layers of diverse cells found at every node,” says Sabbagh, his own eyes lighting up.

His research earned him a coveted spot on the Forbes “30 under 30” list, generating enormous visibility, including in the Arab world, adding visitors to his already robust X (formerly Twitter) account, which has more than 9,200 followers. “The increased visibility lets me use my voice to advocate for the things I care about,” he says.

“I need to make this mean something positive, not just for me, but in as broad a way as possible for other people.” — Ubadah Sabbagh

Those causes range from promoting equity and inclusion in science to transforming the American system of doing science for the betterment of science and the scientists themselves. He cofounded the nonprofit Black in Neuro to celebrate and empower Black scholars in neuroscience, and he continues to serve on the board. He is the chair of an advisory committee for the Society for Neuroscience (SfN), recommending ways SfN can better address the needs of its young members, and a member of the Advisory Committee to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director working group charged with re-envisioning postdoctoral training. He serves on the advisory board of Community for Rigor, a new NIH initiative that aims to teach scientific rigor at national scale and, in his spare time, he writes articles about the relationship of science and policy for publications including Scientific American and the Washington Post.

Still, there have been obstacles. The same year Sabbagh received the NIH F99/K00 Award, he faced major setbacks in his application to become a citizen. He would not try again until 2021, when he had his PhD in hand and had joined the McGovern Institute.

An MIT postdoc and citizenship

Sabbagh dove into his research in Guoping Feng’s lab with the same vigor and outside-the-box thinking that characterized his previous work. He continues to investigate the thalamus, but in a region that is less involved in processing pure sensory signals, such as light and sound, and more focused on cognitive functions of the brain. He aims to understand how thalamic brain areas orchestrate complex functions we carry out every day, including working memory and cognitive flexibility.

“This is important to understand because when this orchestra goes out of tune it can lead to a range of neurological disorders, including autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia,” he says. He is also developing new tools for studying the brain using genome editing and viral engineering to expand the toolkit available to neuroscientists.

The environment at the McGovern Institute is also a source of inspiration for Sabbagh’s research. “The scale and scope of work being done at McGovern is remarkable. It’s an exciting place for me to be as a neuroscientist,” said Sabbagh. “Besides being intellectually enriching, I’ve found great community here – something that’s important to me wherever I work.”

Returning to the Middle East

While at an advisory meeting at the NIH, Sabbagh learned he had been selected as a Young Arab Pioneer by the Arab Youth Center and was flown the next day to Abu Dhabi for a ceremony overseen by Her Excellency Shamma Al Mazrui, Cabinet Member and Minister of Community Development in the United Arab Emirates. The ceremony recognized 20 Arab youth from around the world in sectors ranging from scientific research to entrepreneurship and community development. Sabbagh’s research “presented a unique portrayal of creative Arab youth and an admirable representation of the values of youth beyond the Arab world,” said Sadeq Jarrar, executive director of the center.

“There I was, among other young Arab leaders, learning firsthand about their efforts, aspirations, and their outlook for the future,” says Sabbagh, who was deeply inspired by the experience.

Just a month earlier, his passport finally secured, Sabbagh had reunited with his family in the Middle East after more than a decade in the United States. “I had been away for so long,” he said, describing the experience as a “cultural reawakening.”

Sabbagh saw a gaping need he had not been aware of when he left 14 years earlier, as a teen. “The Middle East had such a glorious intellectual past,” he says. “But for years people have been leaving to get their advanced scientific training, and there is no adequate infrastructure to support them if they want to go back.” He wondered: What if there were a scientific renaissance in the region? How would we build infrastructure to cultivate local minds and local talent? What if the next chapter of the Middle East included being a new nexus of global scientific advancements?

“I felt so inspired,” he says. “I have a longing, someday, to meaningfully give back.”