Where did that sound come from?

MIT neuroscientists have developed a computer model that can answer that question as well as the human brain.

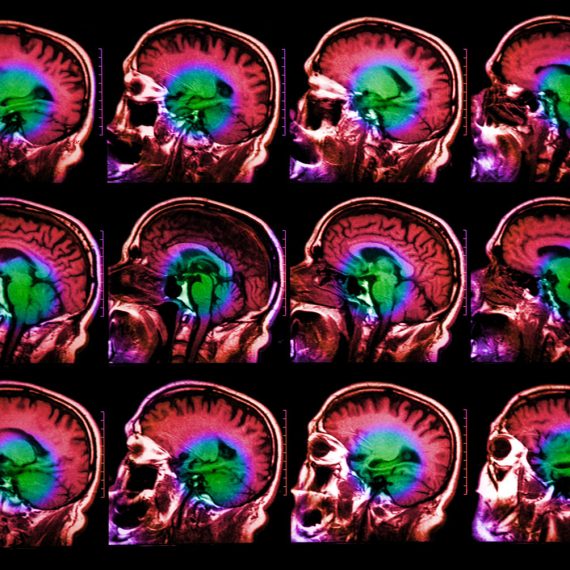

The human brain is finely tuned not only to recognize particular sounds, but also to determine which direction they came from. By comparing differences in sounds that reach the right and left ear, the brain can estimate the location of a barking dog, wailing fire engine, or approaching car.

MIT neuroscientists have now developed a computer model that can also perform that complex task. The model, which consists of several convolutional neural networks, not only performs the task as well as humans do, it also struggles in the same ways that humans do.

“We now have a model that can actually localize sounds in the real world,” says Josh McDermott, an associate professor of brain and cognitive sciences and a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research. “And when we treated the model like a human experimental participant and simulated this large set of experiments that people had tested humans on in the past, what we found over and over again is it the model recapitulates the results that you see in humans.”

Findings from the new study also suggest that humans’ ability to perceive location is adapted to the specific challenges of our environment, says McDermott, who is also a member of MIT’s Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines.

McDermott is the senior author of the paper, which appears today in Nature Human Behavior. The paper’s lead author is MIT graduate student Andrew Francl.

Modeling localization

When we hear a sound such as a train whistle, the sound waves reach our right and left ears at slightly different times and intensities, depending on what direction the sound is coming from. Parts of the midbrain are specialized to compare these slight differences to help estimate what direction the sound came from, a task also known as localization.

This task becomes markedly more difficult under real-world conditions — where the environment produces echoes and many sounds are heard at once.

Scientists have long sought to build computer models that can perform the same kind of calculations that the brain uses to localize sounds. These models sometimes work well in idealized settings with no background noise, but never in real-world environments, with their noises and echoes.

To develop a more sophisticated model of localization, the MIT team turned to convolutional neural networks. This kind of computer modeling has been used extensively to model the human visual system, and more recently, McDermott and other scientists have begun applying it to audition as well.

Convolutional neural networks can be designed with many different architectures, so to help them find the ones that would work best for localization, the MIT team used a supercomputer that allowed them to train and test about 1,500 different models. That search identified 10 that seemed the best-suited for localization, which the researchers further trained and used for all of their subsequent studies.

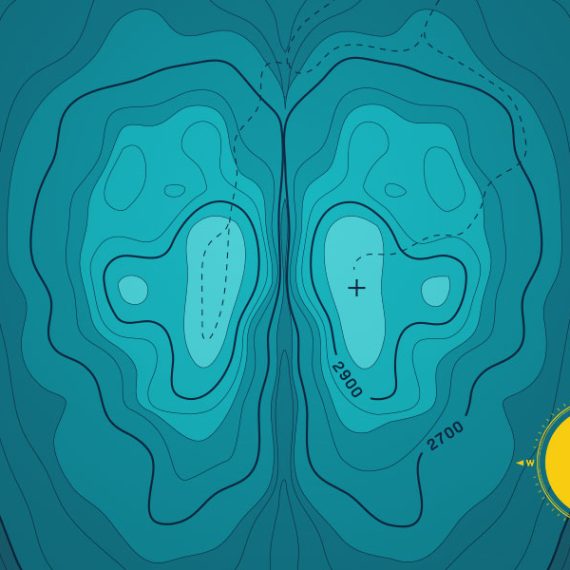

To train the models, the researchers created a virtual world in which they can control the size of the room and the reflection properties of the walls of the room. All of the sounds fed to the models originated from somewhere in one of these virtual rooms. The set of more than 400 training sounds included human voices, animal sounds, machine sounds such as car engines, and natural sounds such as thunder.

The researchers also ensured the model started with the same information provided by human ears. The outer ear, or pinna, has many folds that reflect sound, altering the frequencies that enter the ear, and these reflections vary depending on where the sound comes from. The researchers simulated this effect by running each sound through a specialized mathematical function before it went into the computer model.

“This allows us to give the model the same kind of information that a person would have,” Francl says.

After training the models, the researchers tested them in a real-world environment. They placed a mannequin with microphones in its ears in an actual room and played sounds from different directions, then fed those recordings into the models. The models performed very similarly to humans when asked to localize these sounds.

“Although the model was trained in a virtual world, when we evaluated it, it could localize sounds in the real world,” Francl says.

Similar patterns

The researchers then subjected the models to a series of tests that scientists have used in the past to study humans’ localization abilities.

In addition to analyzing the difference in arrival time at the right and left ears, the human brain also bases its location judgments on differences in the intensity of sound that reaches each ear. Previous studies have shown that the success of both of these strategies varies depending on the frequency of the incoming sound. In the new study, the MIT team found that the models showed this same pattern of sensitivity to frequency.

“The model seems to use timing and level differences between the two ears in the same way that people do, in a way that’s frequency-dependent,” McDermott says.

The researchers also showed that when they made localization tasks more difficult, by adding multiple sound sources played at the same time, the computer models’ performance declined in a way that closely mimicked human failure patterns under the same circumstances.

“As you add more and more sources, you get a specific pattern of decline in humans’ ability to accurately judge the number of sources present, and their ability to localize those sources,” Francl says. “Humans seem to be limited to localizing about three sources at once, and when we ran the same test on the model, we saw a really similar pattern of behavior.”

Because the researchers used a virtual world to train their models, they were also able to explore what happens when their model learned to localize in different types of unnatural conditions. The researchers trained one set of models in a virtual world with no echoes, and another in a world where there was never more than one sound heard at a time. In a third, the models were only exposed to sounds with narrow frequency ranges, instead of naturally occurring sounds.

When the models trained in these unnatural worlds were evaluated on the same battery of behavioral tests, the models deviated from human behavior, and the ways in which they failed varied depending on the type of environment they had been trained in. These results support the idea that the localization abilities of the human brain are adapted to the environments in which humans evolved, the researchers say.

The researchers are now applying this type of modeling to other aspects of audition, such as pitch perception and speech recognition, and believe it could also be used to understand other cognitive phenomena, such as the limits on what a person can pay attention to or remember, McDermott says.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.