Josh McDermott seeks to replicate the human auditory system

Computer models that mimic humans’ extraordinary hearing abilities could improve treatments for hearing loss.

The human auditory system is a marvel of biology. It can follow a conversation in a noisy restaurant, learn to recognize words from languages we’ve never heard before, and identify a familiar colleague by their footsteps as they walk by our office.

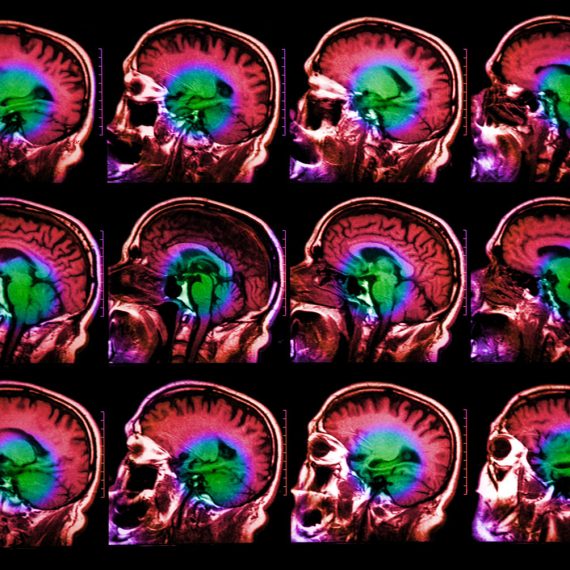

So far, even the most sophisticated computational models cannot perform such tasks as well as the human auditory system, but MIT neuroscientist Josh McDermott hopes to change that. Achieving this goal would be a major step toward developing new ways to help people with hearing loss, says McDermott, who recently earned tenure in MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences.

“Our long-term goal is to build good predictive models of the auditory system,” McDermott says.

“If we were successful in that goal, then it would really transform our ability to make people hear better, because we could design a computer program to figure out what to do to incoming sound to make it easier to recognize what somebody said or where a sound is coming from.”

McDermott’s lab also explores how exposure to different types of music affects people’s music preferences and even how they perceive music. Such studies can help to reveal elements of sound perception that are “hardwired” into our brains, and other elements that are influenced by exposure to different kinds of sounds.

“We have found that there is cross-cultural variation in things that people had widely supposed were universal and possibly even innate,” McDermott says.

Sound perception

As an undergraduate at Harvard University, McDermott originally planned to study math and physics, but “I was very quickly seduced by the brain,” he says. At the time, Harvard did not offer a major in neuroscience, so McDermott created his own, with a focus on vision.

After earning a master’s degree from University College London, he came to MIT to do a PhD in brain and cognitive sciences. His focus was still on vision, which he studied with Ted Adelson, the John and Dorothy Wilson Professor of Vision Science, but he found himself increasingly interested in audition. He had always loved music, and around this time, he started working as a radio and club DJ. “I was spending a lot of time thinking about sound and why things sound the way they do,” he recalls.

To pursue his new interest, he served as a postdoc at the University of Minnesota, where he worked in a lab devoted to psychoacoustics — the study of how humans perceive sound. There, he studied auditory phenomena such as the “cocktail party effect,” or the ability to focus on a particular person’s voice while tuning out background noise. During another postdoc at New York University, he started working on computational models of the auditory system. That interest in computation is part of what drew him back to MIT as a faculty member, in 2013.

“The culture here surrounding brain and cognitive science really prioritizes and values computation, and that was a perspective that was important to me,” says McDermott, who is also a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research and the Center for Brains, Minds and Machines. “I knew that was the kind of work I really wanted to do in my lab, so it just felt like a natural environment for doing that work.”

One aspect of audition that McDermott’s lab focuses on is “auditory scene analysis,” which includes tasks such as inferring what events in the environment caused a particular sound, and determining where a particular sound came from. This requires the ability to disentangle sounds produced by different events or objects, and the ability to tease out the effects of the environment. For instance, a basketball bouncing on a hardwood floor in a gym makes a different sound than a basketball bouncing on an outdoor paved court.

“Sounds in the world have very particular properties, due to physics and the way that the world works,” McDermott says. “We believe that the brain internalizes those regularities, and you have models in your head of the way that sound is generated. When you hear something, you are performing an inference in that model to figure out what is likely to have happened that caused the sound.”

A better understanding of how the brain does this may eventually lead to new strategies to enhance human hearing, McDermott says.

“Hearing impairment is the most common sensory disorder. It affects almost everybody as they get older, and the treatments are OK, but they’re not great,” he says. “We’re eventually going to all have personalized hearing aids that we walk around with, and we just need to develop the right algorithms in order to tell them what to do. That’s something we’re actively working on.”

Music in the brain

About 10 years ago, when McDermott was a postdoc, he started working on cross-cultural studies of how the human brain perceives music. Richard Godoy, an anthropologist at Brandeis University, asked McDermott to join him for some studies of the Tsimane’ people, who live in the Amazon rainforest. Since then, McDermott and some of his students have gone to Bolivia most summers to study sound perception among the Tsimane’. The Tsimane’ have had very little exposure to Western music, making them ideal subjects to study how listening to certain kinds of music influences human sound perception.

These studies have revealed both differences and similarities between Westerners and the Tsimane’ people. McDermott, who counts soul, disco, and jazz-funk among his favorite types of music, has found that Westerners and the Tsimane’ differ in their perceptions of dissonance. To Western ears, for example, the chord of C and F# sounds very unpleasant, but not to the Tsimane’.

He has also shown that that people in Western society perceive sounds that are separated by an octave to be similar, but the Tsimane’ do not. However, there are also some similarities between the two groups. For example, the upper limit of frequencies that can be perceived appears to be the same regardless of music exposure.

“We’re finding both striking variation in some perceptual traits that many people presumed were common across cultures and listeners, and striking similarities in others,” McDermott says. “The similarities and differences across cultures dissociate aspects of perception that are tightly coupled in Westerners, helping us to parcellate perceptual systems into their underlying components.”